Disability Pride

Felicity House

By Haley Moss

Haley Moss is Florida’s first openly autistic lawyer and the author of five books that guide neurodivergent individuals through professional and personal challenges. She is currently a speaker, consultant, and neurodiversity advocate for organizations and corporations that seek her guidance in creating an inclusive workplace and a sought-after commentator on disability rights issues. Her articles have appeared in outlets including the Washington Post, Teen Vogue, and Fast Company. Haley’s life experiences, advocacy, and dedication guide her to leave the state of inclusion better than she found it.

Every July, people with disabilities celebrate Disability Pride Month. The month started as a way to remember when the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law. Now, Disability Pride Month is celebrated beyond the U.S. and has a bigger meaning. Today, it celebrates many kinds of disabilities. It honors our shared past, culture, how we depend on each other, and what we give to society. People with disabilities are the largest group of minorities in the world and in the U.S. But it can be hard to see this because there are so many different types of disabilities. The purpose of this post is to shed light on different disabilities and gain a deeper understanding of each other’s differences. Although a full list of all disabilities is not included in this piece, we are all united in the fight for inclusion, civil rights, and accessibility, and as a collective, face ableism regularly.

Historically, disability is seen in two main ways: the medical model and the social model. Most people who do not have disabilities believe in the medical model. This means they often see individuals as the problem, or disability as something to fix. This is done by making people fit in or by medical treatments. Disability pride is new and special because it comes from the social model of disability. This model says that society creates more problems than any health condition. Instead of fixing people, this model says we need to fix unfair systems and remove things that stop inclusion and access in our world. This means that people with disabilities need more chances, understanding, and acceptance.

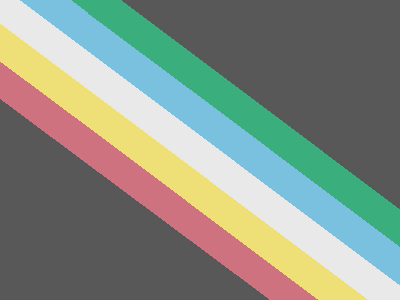

To celebrate Disability Pride Month, there is also a flag you might see at parties or online. The first zigzag flag was made in 2019 by a disabled writer named Ann Magill. It was changed in 2021 to be easier to see for disabled people with vision problems like epilepsy. The order of the colors also helps people who are colorblind or have migraines.

Each stripe on the flag stands for a certain group of disabilities.

The green stripe stands for sensory disabilities. These often have to do with hearing or vision. But they can also include things like sensory processing disabilities.

- Blindness can be different for different people. Some people have low vision and can see some light and shapes. Others cannot see colors. And some have “total blindness,” where the world seems dark. Some, but not all, blind or low vision people use things like white canes or service dogs to be more independent. Of course, like with all disabilities, it’s best to ask if you can help someone or if you can pet a guide dog before doing anything right away.

- Hearing loss and deafness also include many different disabilities and have their own culture. People who are culturally Deaf (with a big “D”) find a sense of belonging through visual ways of talking, like sign language, and shared traditions and values. But not everyone who is deaf or has hearing loss will feel they are part of Deaf culture.

The blue stripe stands for emotional and psychiatric disabilities. This is about mental health. It’s possible to have more than one emotional and/or psychiatric disability, or to get an emotional or psychiatric condition later in life.

- People with emotional and psychiatric disabilities, such as anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders, face a lot of extra judgment in society. Mental health conditions can affect how a person feels. This can lead to feeling sad or nervous. Or it can cause bigger problems like seeing things that are not there, trouble controlling impulses, or risky behaviors. At its worst, emotional and psychiatric disabilities can lead to self-harm or thoughts of suicide. So if you or someone you know is struggling, reach out to a trusted doctor, support person, family member, or caregiver, or call the 988 hotline.

The white stripe stands for invisible or non-obvious disabilities. It also stands for those that are not known or not diagnosed. When we think about non-obvious disabilities, these usually include health conditions and long-term illnesses that we cannot easily see. But they are just as real and hard for the people who have them.

- Some people with disabilities or long-term illnesses are not officially diagnosed. For example, many autistic teenagers are not diagnosed, especially if they are not white. This is also true for other disabilities, where diagnosis can vary based on race, gender, income, and location. This means many people who identify as disabled may not have an official diagnosis, or they might not even realize they are disabled.

- Long-term illnesses and health conditions are complex and not always easy to see. That’s why they are called “invisible” or “non-obvious” disabilities. But this does not make them any less real for the people who live with them. Long-term illnesses like lupus and fibromyalgia can cause tiredness and pain and affect a person’s immune system. Health conditions like diabetes affect a person’s blood sugar and may need regular medicine or insulin.

The yellow (or gold) stripe represents neurodiversity. While autistic people are part of the neurodiversity group, neurodivergence also includes (but is not limited to) people who have learning disabilities, ADHD, intellectual disabilities, and Tourette syndrome. About 19% of people in the U.S. are neurodivergent.

- Neurodiverse conditions affect a person’s brain and how they think. Each of us is different. But difficulties with planning and organizing, sensory differences, and differences with learning and talking are common signs of most types of neurodivergence.

- Neurodiversity is not meant to limit who is included. Instead, it’s a broad term that covers more than just autism, ADHD, and learning differences. Neurodivergence does include intellectual disabilities like Down syndrome, as well as mental health conditions. However, the disability pride flag has separate stripes for emotional and psychiatric disabilities, which can also happen along with other forms of neurodivergence.

The red stripe stands for physical disabilities. Trouble with walking or moving is the most common disability in the U.S. today. Nearly 7% of Americans say they have trouble walking or moving. Physical disabilities can be present at birth, or be the result of birth defects, illnesses, injuries, or age. They do not make a person less capable or necessarily affect their thinking abilities.

- Physical disabilities cover many different things. But most people think of the common image of a wheelchair user on accessible parking signs. Wheelchair users might have limited ability to walk without help (these people are called ambulatory wheelchair users). Or they might find that a wheelchair (manual or power) gives them more freedom than a walker or crutches. Or they might not be able to walk at all. Many different types of disabilities affect mobility, such as cerebral palsy, spinal cord injuries, and paralysis.

- Some physical disabilities only affect a person’s movement. Others might be visible or affect other parts of a person’s life. Some examples are limb differences, where someone might be missing a limb. Or cystic fibrosis, which affects someone’s lungs and ability to breathe.

And finally, the charcoal black/grey background stands for disabled people we remember who have died because of ableism, abuse, neglect, suicide, illness, or eugenics. We also remember some of these losses in our community that happened because of family members and caregivers on March 1, Disability Day of Mourning.

Celebrating Disability Pride is different for everyone. Sharing about the disability flag is just one way to learn about this topic. I know that for me, getting to a point of disability pride has been a journey. When I was a younger autistic person, I felt safer masking, avoiding disclosure, or trying to distance myself from the portrayal of autism as incompetence or an intellectual disability. Now, I know I am very much in community with people who have intellectual disabilities, and whose autism is not the same as my own. Learning more about the achievements and resilience of our community gave me a sense of pride and belonging. Even though I studied disability in college, it was not until the movie Crip Camp came out that I truly felt connected to the larger disability community and our shared history.

There is no single way to celebrate. You can celebrate online, quietly by yourself, if your local community has events or a parade, or if your workplace has speakers or training about disability. Whatever feels most accessible to you, and lets you feel real and take ownership of your disability identity, is what pride is truly about.

To learn more about disability history and pride:

Of course, the best way to learn about disabilities and views that are different from our own as autistic people is to learn from other disabled people. Part of disability pride is also to uplift the voices of disabled people.